- Executive Summary

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1.0 Parking and the Home

- 2.0 The Kent Data

- 3.0 Resident Views

- 4.0 Case Studies

- 5.0 Conclusions & Recommendations

- Bibliography

Sign in

3.0 Resident Views

In order to understand the background to the case-study site observations, a door-to-door survey of residents was undertaken along with two mini focus groups. The survey and focus groups were led by Progressive, a market and social research agency. In this chapter we describe first the survey and then the findings of the focus group.

The survey

The door-to-door survey was undertaken in June 2013 and included 204 responses from people living in estates built in Kent since 2006. The case studies described in Chapter 4 focussed on the some of the estates surveyed .

The survey started by asking people how satisfied they were with their neighbourhood. The overall level of satisfaction was very high with 85% either satisfied or very satisfied and 79% would recommend the estate to a friend. Only slightly fewer people 75% were satisfied with the physical layout of the estate. However when asked specifically about the road layout the figure dropped further and 41% were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied.

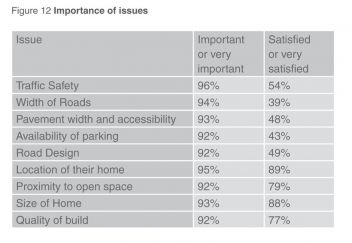

Figure 12

In order to explore these responses people were asked to rank issues in order of importance when considering their neighbourhood and then to rate their neighbourhood against these same issues. As the table shows people considered all of the issues to be more or less important. Many of the issues ranked as most important were those that you would expect; general location, proximity to open space and the size and quality of the house. However of the nine issues ranked by as important or very important, five concerned cars; traffic safety, width of road, pavement width and accessibility, availability of parking, and road design. The lesser-ranked issues were; proximity to public transport, schools and work, the mix of houses and, interestingly, having a garage.

Figure 12

In order to explore these responses people were asked to rank issues in order of importance when considering their neighbourhood and then to rate their neighbourhood against these same issues. As the table shows people considered all of the issues to be more or less important. Many of the issues ranked as most important were those that you would expect; general location, proximity to open space and the size and quality of the house. However of the nine issues ranked by as important or very important, five concerned cars; traffic safety, width of road, pavement width and accessibility, availability of parking, and road design. The lesser-ranked issues were; proximity to public transport, schools and work, the mix of houses and, interestingly, having a garage.

Figure 12 shows the way that people rated each of these issues for their estate. The two tables (Figure 12 and 13) can be compared to show that they are very satisfied with many of the issues that they consider to be most important.

These are all issues that could be assessed when they were considering which house to buy. However the issues ranked important, where people were less happy, largely relate to the car and may have been less evident at the point of purchase particularly for people who bought before the estate was complete.

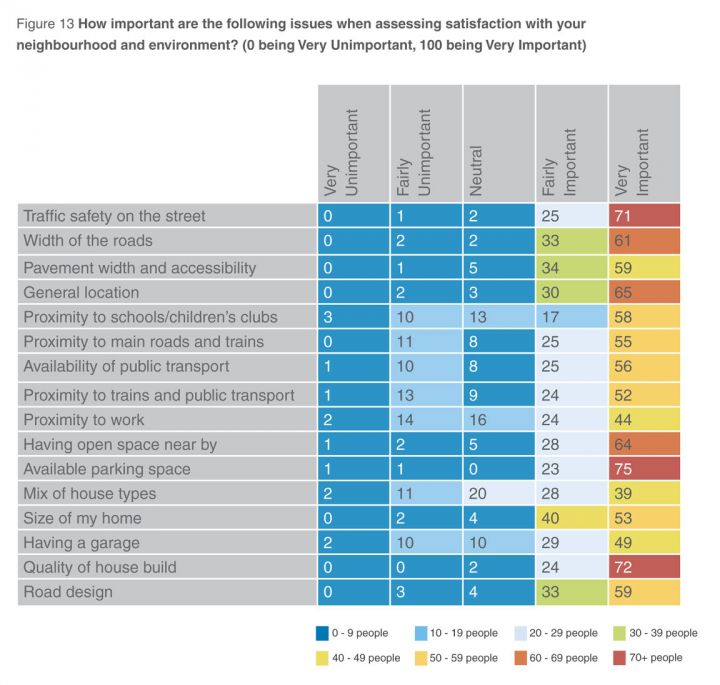

Figure 13

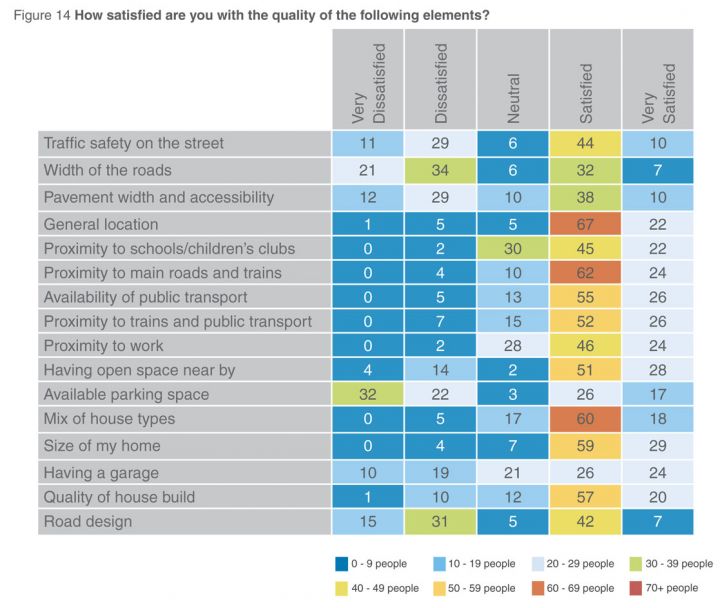

Figure 13 Figure 14

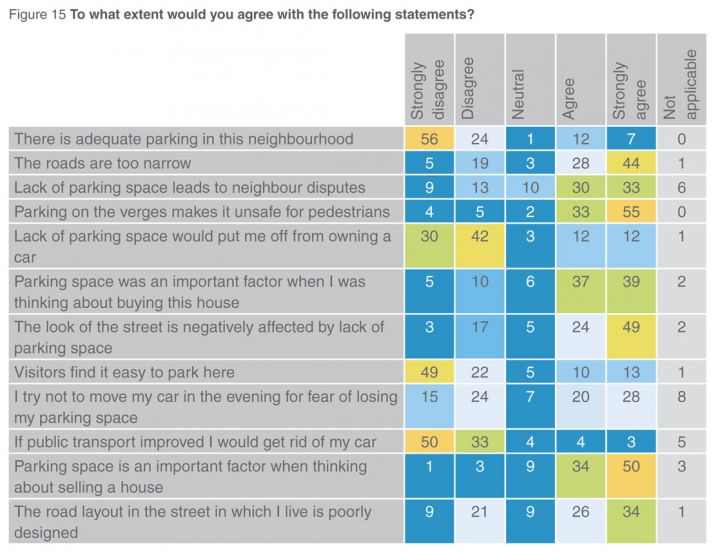

Figure 14 Figure 15

Figure 15The survey then delved deeper into people’s attitudes to these car related issues as shown in Figure 15. This shows that 80% of people felt that there was inadequate parking on the estate and 63% felt that this had led to neighbour disputes. Almost three quarters of people felt that the roads on the estate were too narrow and that parked cars negatively affected the appearance of the street with 88% feeling that cars parked on verges made the area unsafe for pedestrians.

Despite this only a quarter of people said that lack of parking would put them off from owning a car and virtually no one (7%) agreed with the statement that they would get rid of their car if public transport were improved.

Three quarters said that parking had been an important issue when buying their house increasing to 84% of people who felt that it would be an important factor when they came to sell. Half suggested that they would try and avoid using their car in the evening for fear of losing their space and only 23% said that visitors found it easy to park. Overall 60% felt that the street layout of their estate was poorly designed.

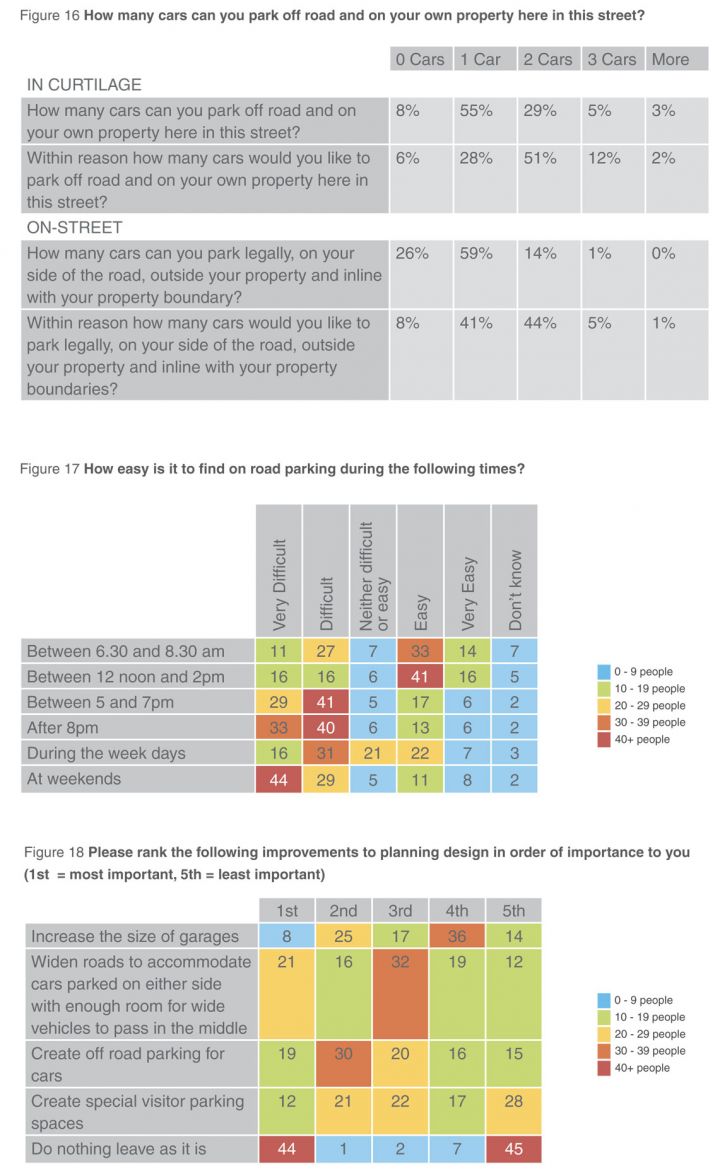

The survey went on to ask people about where they parked. As Figure 16 shows just over half of the respondents were able to park one car off road on their property while 37% could park 2 or more. This suggests an actual off street parking ratio of 1.41 vehicles per unit. When asked how many vehicles they would like to be able to park off street just over half wanted to be able to park two cars and 14% wanted more than this. The desired off street parking ratio was therefore 1.77 vehicles per unit.

These figures are increased by the answers to the question about parking on-street. 59% of people parked one car on the street outside their home and half of respondents wanted the ability to park two or more cars on the street. This would raise the actual parking ratio to 2.3 vehicles per unit and the desired ratio to a huge 3.28 vehicles per unit.

42% of respondents had a garage but of these only 41% used it to park their car. The main reasons cited by those people for not using their garage was that it was too small (48%) or that they preferred to use it for other uses (44%).

Figure 17 indicates the times of the day when the parking problems are most apparent. It is clear that evening and weekends are the most difficult times with 70% of respondents having problems finding a parking space at these times.

When asked to prioritise possible improvements the results were evenly spread with the greatest number of people giving top priority to leaving the estate as it is. However the greatest number of priorities 1 and 2 were given to increasing the amount of off street parking.

Focus Groups

The two focus groups involved 9 individuals drawn from the estates described in Chapter 4. The discussions took place in May 2013 in Maidstone Kent and were moderated by Progressive.

The nine individuals involved in the groups represented households containing 22 adults and 9 children. The reason for the high number of adults was the fact that four of the households had adult children still living at home. In total the nine households owned 21 cars, pretty much one for every adult. Indeed one household had four cars for the mother, father and their two grown-up sons and also had to find two further parking spaces for the sons’ girlfriends when they visited.

The individuals had lived in their homes for between 18 months and six years. One lived in a terraced house, one in an apartment and the remainder in a mix of semi detached and detached units, all had bought the house new from the developer. The initial part of the discussion focused on the reasons why they had bought their house and how they felt about their neighbourhood.

The main reason for buying a new house was that there was no maintenance and it was seen as being more energy efficient than a second-hand property. They were attracted to the ease of buying without worrying about there being a chain of buyers and sellers and felt that the price had been competitive. Many mentioned the size of the houses as well as the fact that the house had a garage.

They chose the estate for a combination of privacy and convenience. They liked the fact that it was out of London, was quiet and had parkland and countryside on the doorstep. On the other hand they mentioned proximity to friends and family, to schools, to a train station or motorway junction and also accessibility to a local town centre. When asked about the best aspect of their estate they mentioned space, landscape and countryside. When asked about the worst aspect the first thing mentioned, spontaneously by all participants was parking.

One of the households had bought their house off plan and all of the others had moved in before the estate was completed. The extent of parking problems was not therefore apparent when they were considering whether to buy. The discussion of parking was vociferous, emotive and the opinions expressed were unanimous. They considered that fundamentally there were not enough parking spaces allocated for each house. As a result of this cars were forced to park on the streets, which were not wide enough to accommodate this. This resulted in parking chaos with vehicles parked partly on pavements, verges and landscaped areas. This had a range of consequences:

- Pavements were blocked and couldn’t be used by buggies or wheel chairs.

- Landscaped areas were churned up and muddy

- Streets became dangerous particularly for children who therefore couldn’t play out.

- Cars had difficulty manoeuvring leading to accidents and scrapes.

- Sometimes parked cars made it difficult to get into legitimate parking spaces.

- Bin trucks and emergency vehicles couldn’t get through (two cases were mentioned where it was claimed that people had died because ambulances couldn’t get to them).

- Garages were under-used because they was no space to get out of their car once they had driven in.

The lack of parking had become the major cause of stress on the estate. Some people said that they were reluctant to go out in the evening because they knew that this would mean losing their parking space. Others said that they would leave work early to make sure they found a parking space and that they would discourage visitors from coming a weekends because they knew that they would not be able to park.

Inevitably this leads to tensions and neighbour disputes as people try and protect their spaces and get annoyed at others parking outside their home, in their spaces. Participants reported tactical parking (across two spaces) to protect a space for another household member. People were parking on their lawn, in some cases even encroaching on their neighbour’s garden. They were double parking in drives and parking courts, parking on turning heads, on corners and junctions obscuring visibility, on pathways and on communal landscape areas. All of the workshop participants considered this behaviour to be antisocial however they all admitted to doing many of these things themselves suggesting that they had no choice.

There were however some parking sins that were considered unacceptable, which the participants reported happening on their estate but did not admit to doing themselves. These included blocking access to other people’s allocated parking spaces and garages, blocking emergency vehicle access points, parking too far from the kerb, parking inefficiently by leaving too much space in front or behind the car, parking large vehicles that take up more than one space, and having multiple cars that have to be parked in front of other people’s homes.

These issues seriously undermined people’s enjoyment of their home. A number of participants suggested that the parking situation had prevented them from selling their house and meant that it was now worth less than they had paid for it. They said that they would never arrange a viewing at the weekend because the parking situation would be too obvious. The majority said that they would not have bought their house if they had known what they know now about the parking situation.

Many of the participants were bewildered about why this should have happened. Some had come from Victorian streets in London with notorious parking problems but said that the current situation was worse. They suggested that their estates were not fit for modern households with adult children at home and couldn’t understand, when so much effort had been put into the design of the home, how the situation with the roads could have been allowed.

Most saw the problem as being greedy developers in cahoots with the council cramming too many homes into schemes and thereby creating problems of which parking was the most obvious. Their suggestions included creating wider roads so that people could park on both sides, building bigger garages, developing at lower densities, providing less open space, and (obviously) providing more parking. They all rejected the idea of resident parking schemes that they saw as penalising them for the mistakes of others.

In a sense this is an inevitable consequence of the type and location of the housing. All of the participants were dependent on their car. Despite them citing access to public transport as one of the reasons for choosing the estate none of them used it. Only one participant had commuted to work by train but even he now drove like every other member of the group. The group saw it as inevitable that every adult needed access to a car if you lived outside London. They were very resistant to the idea that they should give up their car, even if public transport were available. It was clear that the restrictions on parking are having no influence on decisions about car ownership, particularly since they suggested that car accessibility to the estate was very good and congestion not a problem (until you arrived home).

The focus groups were useful in two respects; to gain an understanding of the issues, and inform the development of the questionnaire for subsequent extensive survey.